|

|

|

|

|

|

Tea-Time at the Parc

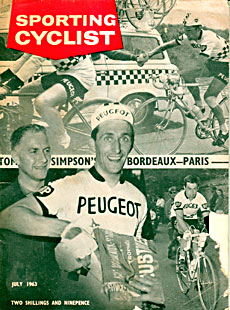

J. B. Wadley on Tom Simpson’s Sensational Bordeaux-Paris; Sporting Cyclist July 1963

|

|

|

|

IT was the last 10min of Bordeaux-Paris. In the Press cars we tore over the Pont de Sevres, along the Avenue de la Reine, swung round the last sharp bends to the forecourt of the Parc des Princes. We sprinted to the little gate on the right, past the riders cabins, down the ramp under the track and out into the centre of the Parc des Princes, cool, green grass surrounded by 454m of pinkish track, and covered stands. Some 30.000 people were in the stands, but the ribbon of cement was empty, reserved for the winner of the 62nd Derby of the Road. IT was the last 10min of Bordeaux-Paris. In the Press cars we tore over the Pont de Sevres, along the Avenue de la Reine, swung round the last sharp bends to the forecourt of the Parc des Princes. We sprinted to the little gate on the right, past the riders cabins, down the ramp under the track and out into the centre of the Parc des Princes, cool, green grass surrounded by 454m of pinkish track, and covered stands. Some 30.000 people were in the stands, but the ribbon of cement was empty, reserved for the winner of the 62nd Derby of the Road.

We knew who he should be, must be - but by some terrible mishap. still might not be. We had last seen him five miles from the finish, well away from his nearest rivals, going like mad and a certain winner barring accidents. For my part I refused to believe it all until I had seen him safely over the finishing line.

There was not long to wait. The commotion outside grew to a roar, the traditional gun shots were fired, a kind of conductor's cue to the trackside crowd to take over the chant of victory to Tom Simpson, first British winner of Bordeaux-Paris since 1896.

Tom was so far ahead of his rivals that he could have taken 5min over that last lap and still won. But unknown to us at the time, he had other plans. Almost for the first time for 200 miles he had spoken to his pacemaker, Fernand Wambst. about 2km from the Parc des Princes:

"We'll sprint for the prime!"

The prime was for 100,000 francs, £80 or so, a nice little sum, but really "peanuts" compared with the £1,000 first prize, big bonuses from his many sponsors, and the string of track contracts awaiting his signature.

It was a tremendous thrill seeing Tom sprint that last lap, for it proved that he had really won the Derby at a canter. Some may argue that the race was not all that important without Anquetil, Van Looy, Altig and Stablinski - and indeed, that argument has had its points for many years now.

But that last lap of the Parc des Princes, and that last hour on the road from the Dourdan hill %%here he soared away from his rivals, proved that Tom Simpson would have won the 62nd Bordeaux-Paris no matter who had been there. And so - the old-timers told me afterwards - could a man of Tom's class have won many, many of the 61 that have gone before. . . .

|

|

|

WAS the importance of Bordeaux-Paris on the wane? I wondered this for only a minute or two after my arrival in the capital of the wine country. I walked along the broad, sunny Allees de Tourny to the crossroads of the Cours de Verdun, where on the corner I spotted the Cafe de France, operations centre for the 62nd Derby of the Road.

Apart from two or three banners. there were no signs of unusual activity. True, it was not yet two o'clock on the Saturday afternoon. and official activities did not begin until four. But I remembered my last Bordeaux-Paris. in 1956, when the headquarters was in a sizeable indoor sports arena, the outside of which was well plastered with banners of all the firms connected in any way with the promotion, headed, of course, by "L'Equipe", the organising newspaper.

But today, H.Q. was Just a typical cafe with its terrasse. In the sun with a drink I asked the waiter if there was some big courtyard at the back of the cafd where the Bordeaux-Paris "control" would take place.

"No sir. It is here in the very place where you are sitting."

Then I realised the reason for the modest nature of the 1963 headquarters. On that 1956 "Derby of the Road," the race was Derny-paced throughout its 350 or so miles; this time the pace-makers did not come on to the scene until 150 miles had been covered. The most important H.Q. of the race was, therefore, not at Bordeaux itself, but at the takeover town of Chatellerault. At Bordeaux the officials would be concerned merely with the checking of the bicycles on %Nhich the 15 competitors started, a comparatively simple task; at Chatellerault their colleagues had the more complicated Derny machines to deal with, and their experienced and (often) astute drivers.

At this point another difference between the 1956 Bordeaux-Paris and the 1963 version occurred to me, and that was in the paced-all-the-way race we were able to get in an hour or two in bed before the 4.30 a.m. start: the 1963 partial-paced was scheduled to start at 2 a.m. . . .

I left the cafe to carry on its normal business for a while, but when I came back at four o'clock, just as the garcon had said. my little corner had been taken over by the officials, who were getting out their papers and settling down at tables. The place now looked more like a "control" with additional publicity banners hanging, and small barriers to fence off the area. They were hardly needed for the two-hour session, for the formalities concerned not the men of Bordeaux-Paris, but their bicycles. True, Peter Post and Van Est looked in for ten minutes, but this was only because they wanted to go for a short ride and had their bikes checked on the way. The other riders were resting in their hotels.

The technical formalities at Bordeaux were simple. The machines had to be those of "type in current use". The only measurement taken was that between the bottom bracket and the front spindle, which had to be at least 58cm. The idea, of course, is to prevent riders getting up too close to their pace. A big rider's machine - such as Post's - was easily within the limits, while little Le Menn's only just made it. Apart from the big chainwheels - 56 was the most popular "saucer" in use - the machines were normal enough, the only obvious difference between them being in colour. Violet. Mercier's; bronze, :Mann's; red. Sauvage-Lejeune's; blue, Gitane's; black Bertin's; and the cream, Peugeot's liberally decorated with black squares, domino fashion.

Apart from the 58cm test, the only further treatment the bicycles received was to have an official seal fixed around the seat cluster, and another on the front forks. Thus it would be easy for a commissaire to spot if a rider was using a machine that bad not been checked.

From M. Gaston Plaud, directeur sportif of the Peugeot team. I learned that his four riders would be having their big pre-race meal at 11.30 p.m. I was there an hour earlier. Down in the kitchen of the hotel, M. Plaud's team of helpers had more or less taken over, and were busy filling bidons and preparing rations for riders, pace-makers and helpers for the long day in the saddle. It was all reminiscent of preparation for a "24" or an "End-to-End."

I sat in the lounge of this first-class hotel watching helpers carrying the vast stock of provisions, spare wheels, tyres and clothing to the vans outside. A mechanic sat with me for a few minutes. "What has happened to Brian Robinson?" he asked. "We had his Peugeot bikes all ready for him for the road season, and they were hanging up in the service des courses. In the end, Hoevenaers took them over. A pity Brian has retired. A good rider and a nice fellow."

Then one of the trainers joined us. I had the temerity to remark that the unpaced part of Bordeaux-Paris, the first 250km to Chatellerault, seemed a mere formality. The race never really started until the Dernys took over.

"Bordeaux-Chatellerault nothing?" the newcomer said. "I think it is something very important indeed. They may all arrive at Chatellerault together, but they will not all arrive in the same condition. Those who have been the best looked after, and who have best looked after themselves for eight hours or more, will be the best equipped for the final battle behind the pace-makers.

"You might as well say," continued my critic severely, "that because a sprint race is won in the last 200 metres. the first 800 metres at a slow pace do not matter. They do - and so do the 250km from here to Chatellerault."

At 11.20 p.m., down the stairs came track-suited Tom Simpson. The theory was, he told me, that he should sleep all day. In fact he hadn't slept at all. Now he had to cat, and wasn't so sure that he could. Earlier on he had eaten a mixture in which honey was largely involved, and he believed that had caused the sweating and spell of dizziness.

“The last time I felt like that was just before the world road championship in 1960," he said. "I turned out to be in top form really that day, so perhaps this is no cause for alarm. Nerves, maybe."

I went with him to the restaurant and sat at a neighbouring table while he and his team-mates Forestier, Rentmeester and Hoevenaers bad their meal, the disposal of which caused Tom no bother after all. Menu: vegetable soup; raw grated carrots; a big underdone steak with boiled rice; two yoghurts. (The others took sugar with theirs, Tom did not.) No wine, but mineral water (Badoit) into which Tom squeezed the juice from slices of fresh lemons. The meal lasted 45min or so, during which time I don't think bikes were mentioned once, and Bordeaux-Paris not at all. Cars and their performances were the favourite topics.

Then, up in his hotel room, Tom in no way acted like the man about to start the most important race of his career. He went leisurely about packing his valise with things not wanted on the 350-mile voyage ahead, and looked over his spare clothing for the race. A short length of zip half-way up the side of his new long-sleeved Peugeot jerseys puzzled him (later he told me it was an idea of Gaston Plaud's for pulling them off easily).

He blacked his shoes carefully, finding as he did so that the laces wanted changing. He rummaged in a musette. "Good girl," he muttered as he found a new pair. Helen, his wife, although with important and happy events of her own to think about, had remembered to keep that musette stocked with the small but important items of her husband's trade. Tom talked of Helen, and the other two Simpson girls: Jane, 14 months, and Joanne, five days; how one day they might settle in Australia. "I may go to Australia next winter to race," Tom said. "A couple of open-air six-day races with John Tresidder, and the Sun Tour."

What if he won Bordeaux-Paris. Would he ride the Tour de France?

"Almost certainly not," he replied. "I would concentrate on the world road championships, pursuit and road. Anything happening at home this week-end?"

I told him that London-Holyhead (that British Bordeaux-Paris) had finished a few hours ago, that the, 25 miles championship would begin in an hour or two.

Then leaving Tom to complete his preparations I went off to the headquarters zone which now, at 1.30 a.m., was alive with activity. Le Menn was the first rider to arrive. wearing the lightly tinted glasses favoured by most of the field, except the two Merciers, who sported the goggles in vogue in the days of their directeur sportif, Antonin Magne. A big cheer greeted the arrival of Tom in his tammy, plentiful jerseys and heavy leg warmers. After signing on, Tom withdrew from the crowd: somebody brought a chair front the cafe and on it he relaxed for the last five minutes before the call to the line.

Then the whistle, the line-up of the 15 riders, the neutralised depart for 2km along the quays during which Peter Post does a mock pace-following act behind a gendarme's motor bike, over the Garonne by the St. Pierre Bridge behind the car of assistant race director Albert De Wetter, who drops his flag at 1.58 a.m.- and the 62nd Bordeaux-Paris has begun.

|

|

|

There is a long hill out of Bordeaux. with a cycle path alongside. As the little peloioll of competitors pedals easily up the slope, a score of moped riders buzz up on their right to enjoy a 5min close-up of the jockeys of this Derby of the Road. There are big crowds out to cheer them until the big cross-roads at Les Quaire Pavillions (until two years ago always the starting point of Bordeaux-Paris) - and then out into the open country. Not that the road is deserted. Plenty of people (many in dressing-gowns) still up to see 15 riders take no more than 15sec to go by. . . . The roads are not closed. The pocket-peloton keeps well to the right, and now and then the motor cycle police pilot ordinary road users by, but their colleagues ahead have brought the oncoming traffic to a halt, which is just as well since most of it comprises huge lorries and trailers.

The 15 bowl along at evens, a motley crowd in their woolly bonnets and over-clothing, chrome-plated fittings flashing in the car lights, sturdy legs economically, turning gears in the mid-70s. Now and then the Belgian and French TV cars go alongside, a technician in the rear scat holding out high-powered lamps. The effect is quite fascinating. Shadows of riders and machines are thrown sharply on to the adjacent vineyards which, themselves flooded with this artificial light, look like a great, green sea as wave after wave of vines ripple by.

Dawn. mist, birdsong in the hedgerows, chatter among some of the 15. At 5.20 up comes the sun slightly to our right, a great red plateful of it rising over the town of Angouleme, where the first feeding is allowed direct from the team cars.

Assistant race director De Wetter is in car No. 2. 1 am in car No. 3 with his co-assistant. Nicely placed. too, right behind the riders. able to judge their various styles from close quarters. Tom is pedalling comfortably. I reflect that in the days of G. P. Mills, who won the first Bordeaux-Paris in 1891 and in 1896 when Welshman Arthur Linton dead-heated with Gaston Riviere, the dropping of the ankle at the top of the pedal stroke was the style of the champions. Here, now, are 15 stars all with ankles raised around the entire orbit. An Englishman. three Belgians. five Dutchmen and six Frenchmen can't be wrong. .'

From time to time riders in ones and twos have stopped by the road-side "for little personal needs" as French Pressmen so nicely put it. About half-past seven Tom stops, and as he comes back alongside I can see he is in good shape.

"Nearly went to sleep three times in the first hour or two." he says. "I shall be glad when the race really starts."

Before going right back into the bunch Tom rides hands off, doffs his top jersey, slings it round his neck with the sleeves tied umpire fashion where it remains until his team car comes up to collect. In another 50km or so, just south of Poitiers, practically the entire field hurriedly dismounts in front of their parked team-vans for the traditional "striptease" and hurried rub down. We are now approaching the take-over town of Chatellerault.

Until now there have been few Press cars behind us. Now they are beginning to build up, because whatever my trainer friend thinks of the unpaced part from Bordeaux to Chatellerault, my colleagues do not think it worth while following it. In a way they are right, for while it is heroic to stay up all night watching the whole affair, the man who has had a good night's sleep will write a better story immediately after the race than his drowsy colleague.

On the outskirts of Chatellerault now. From a bunch of 15, the riders become a string, gradually warming up the pace and almost sprinting the final unpaced miles through the twisting town. Underneath the big overhead banner in the Boulevard Blossac are the 15 Dernys, which accelerate as the riders aproach and contact is made. Through the puffs of smoke from the buzzing machines I spot riders and their pace-makers shaking hands before getting down to business. Behind us are 15 reserve pace-makers ready to take over.

At this moment there are 299 kilometres of paced riding ahead to the Parc des Princes, and almost immediately the red flag goes up in car No. 1, signifying that a break is in progress. Incidentally, M. Jacques Goddet is wielding that flag; as it is the first time we have seen him, it may prove, after all, that Bordeaux-Paris really does begin at Chatellerault!

It is easy to find who is in the break by establishing who is not in it.... Six riders are not: Post, Van Est, De Roo, Lefebvre, Hoevenaers and (I am glad to see) Simpson. News soon comes that Jean Forestier has "gone" from the start, and the other eight (Delon, Maliepard, Nijs, Melckenbeck, Delberghe, Le Menn, Beuffeuil and Rentmeester) are grouped a minute or so behind. As the Simpson group is only riding at 40km.p.h. it is not surprising to hear that Forestier is running away at the front and at Saint Maure (264km to go) he has a lead of 6min. This. of course, is no cause for alarm to Simpson. since Forestier is his team-mate. Moreover, Tom is riding with the two race favourites, De Roo and Post, and will be ready to follow any moves they make to reduce the margin.

It is not quite so hot as we expected, the wind slightly from the north. Forestier battles on, but finally is caught after a 142km break and dropped by Maliepard and Rentmeester. the latter, again, being a team-mate of Tom's. When the lead gets to nine minutes, and there is still no serious reaction from Post and De Roo. I begin to get uneasy. Has pace-maker Fernard Wambst, in his anxiety to curb the impetuosity of follower Simpson, become too cautious? It seems that if Tom wants to get up there to the front he will have to go on his own, since neither Post nor De Roo seems inclined or able. As for that other great Dutchman, Wim Van Est, whose great calf muscles are almost touching his down-tube bidon, he is suffering and will be dropped soon.

Then Simpson attacks, or rather Wambst steps up the pace. It is the first move of a two-pronged effort destined to make cycling history.

Without fuss or bother, the Anglo-French "tandem" moves up relentlessly at 35 m.p.h. towards the front, dropping the failing Forestier and the other "intermediaries" on the way. As .he spires of Chartres Cathedral come into view so does Tom see ahead on the road his two objectives: Rentmeester and Maliepard.

Beyond the cathedral city Delberghe comes back from behind, and at Ablis we are astonished to see little Le Mean fight his way back, too. Five men in the front, then, with 64km to go!

I have now changed cars. The assistant director in my first has necessarily to keep behind with the stragglers. I have come to see an Englishman win Bordeaux-Paris, and I mean to do so. Finding another seat is dead easy. Everybody wants to get a story from the only English journalist in the race! My new car has a distinguished "captain"; Pierre Chany, of "I'Equipe" (the man who last year described me as J. B. Wadley of the English magazine "Cycling!"

"Who, do you fancy, Pierre?" I ask.

"Delberghe or Simpson. If Simpson goes too early, the more regular Delberghe might fight back. Dourdan holds the key to the situation”.

Dourdan, chief obstacle of the Valley of the Chartreuse we are now approaching. Dourdan of the narrow streets and cobbled base to the hill that has played a vital part so many times in Bordeaux-Paris....

Beyond the other cars we can see the group of five. Pierre turns on the car radio and we hear the commentator from the front giving the greatest sporting news I have ever heard over the air. "Simpson attacks on the lower slopes of Dourdan .. . Delberghe resists for a short time. then is dropped by his Derny . .

Simpson pedals easily on, while the other four are stretched out behind ... Simpson 100 metres in the lead . . . well away . . . 200m at the summit...."

This is the critical moment of the whole race. Will Chany's prediction come true? Will Delberghe fight to regain his lost ground and knock out Tom in The last round of this 15-hour International contest?

It is the Valley of the Chevreuse of the great days. The woods packed with spectators, picnic tables abandoned. They've cheered Gauthier four times, Van Est three times, Bobet once to victory. Now they really roar this English Tommy on.

The radio again. ". . . Here now at Limours at the top of the hill, with 36km to go, Tom Simpson has a two-minute lead. He is riding so strongly that, bearing accidents, he must win Bordeaux-Paris. Behind the riders are beaten. . . ."

Despite the narrow roads, Press colleagues are drawing up alongside with the thumbs-up sign. "Tom is the first man!" sings out Jos Van Landeghem. "Bravo Tom - il est formidable" from Louison Bobetwith Jean in the Radio Luxembourg car. From M. Jacques Goddet is an undisguised expression of delight, and Rene de Latour and Roger Bastide are giving the boxer's victory sign.

But hold it.... This race isn't over yet. Hasn't Rene himself told us in these pages of mighty Bordeaux-Paris collapses of the past, of men riding like trains one minute and dead to the world the next? There's 20 miles to go, ups and downs, through towns, round nasty corners, dogs might rush out, a front tyre burst. Tom has nearly won three classics this year, and there is always the danger that he may still only nearly win this. Tom knows it, too, and so does Wambst. They take the corners cautiously (we have now passed the four others, who seem resigned to fighting for second place) and at last are safely in Versailles where thousands line the roadside. But hold it.... This race isn't over yet. Hasn't Rene himself told us in these pages of mighty Bordeaux-Paris collapses of the past, of men riding like trains one minute and dead to the world the next? There's 20 miles to go, ups and downs, through towns, round nasty corners, dogs might rush out, a front tyre burst. Tom has nearly won three classics this year, and there is always the danger that he may still only nearly win this. Tom knows it, too, and so does Wambst. They take the corners cautiously (we have now passed the four others, who seem resigned to fighting for second place) and at last are safely in Versailles where thousands line the roadside.

"We must pass now and get to the finish," says Chant'.

On the famous Cote de Picardie, out of Versailles, we pass our hero, mouth open wide, head and shoulders heaving a bit, but his coup de pedale as steady as ever. The crowds are clapping, cheering and shouting Seem-son. Down to the Seine, over the Pont de Sevres, along the Avenue de la Reine, park the car, under the track up to the crowded Pare des Princes. No time even to get the cameras out of the bag when there is a series of gun shots from the tunnel entrance, the signal that a rider is about to enter.

In he comes, behind Wambst, reserve pace-maker trailing. Tom sprints that last lap to tremendous applause, throws high his hands in the air as he crosses the line as great a Bordeaux-Paris winner as there's been since G. P. Mills won the first in 1891.

Later, at the Peugeot celebration supper, Tom had little appetite and drank carrot juice. Who had helped him most to win Bordeaux-Paris? I asked. "Two men: my Belgian trainer Gus Naessens, and my pacemaker Fernand Wambst," he replied.

Wambst was sitting a few places away, and he told me that their understanding was so great that they hardly spoke a word until 2km from the Parc when Tom called out, "On sprint pour le tour." (We'll sprint for the lap) Earlier, Jean Bobet had told me that Wambst had been carefully selected as Tom's pacemaker. Wambst had paced Kubler to victory in 1953, curbing the Swiss star's tendency to "battle" too much. Simpson is of a similar temperament, and "class," too.

The party did not last very long. Everybody was tired. But I and three Belgian journalists remained at the table. The champagne bottles were there, too. We emptied them promptly. Then Mr. Jerome Stevens of Het Volk ordered another.

"Tom comes from your country. He lives in my town, Ghent. Let us drink to your great compatriot, who I am proud to have as a neighbour," he said."

|

|

|

|