|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A New Way to Paris from Bordeaux

J. B. Wadley International Cycle Sport November 1970

|

|

|

“THE Big Bordeaux Battle - Full Details" said the placard outside the newsagents on the bus route from the airport to the centre of Bordeaux. But when I later bought a copy of Sud Quest I found that this was not the war I had come to report. Indeed in the Alles Tourny I met a press colleague from Brittany who figs been a regular on the Tour de France for some years, and assumed he was there to cover Bordeaux-Paris. “THE Big Bordeaux Battle - Full Details" said the placard outside the newsagents on the bus route from the airport to the centre of Bordeaux. But when I later bought a copy of Sud Quest I found that this was not the war I had come to report. Indeed in the Alles Tourny I met a press colleague from Brittany who figs been a regular on the Tour de France for some years, and assumed he was there to cover Bordeaux-Paris.

"No such luck" he said "I'm here for the Bordeaux by-election. It doesn't take place for another fortnight, but the place is full of journalists. You probably know that the Prime Minister of France, M. Chablan-Delmas is also the mayor of Bordeaux and has held the parliamentary seat for the last 23 years. There are eight other candidates, but the chief opposition is from M. Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber whom all the papers are calling J.J. - S.S."

Bordeaux-Paris, I found, was not front-page news. True it had the "eight- column" treatment in the sports pages of Sud-Quest but the columns were not very deep and most of the remaining space was occupied by reports of the European swimming championships at Barcelona and a preview of that same Saturday night's France-Czechoslovakia football match at Nice. In these events, at least, there was some chance of a French victory, which was more than could be said from a glance at the 16 runners in the 69th Bordeaux-Paris, known as the Derby of the Road.

|

|

|

This was the line-up.

1 PERIN Miche lFagor-Mercier France

2 PROUST Daniel Fagor-Mercier France

3 BEUGELS Eddy Mars-Flandria Holland

4 BODART Emile Mars-Flandria Belgium

5 MORTENSEN Leif Bic Denmark

6 ROSTERS Roger Bic Belgium

7 BRACKE Ferdinand Peugeot-B.P. Belgium

8 DELISLE Raymond Peugeot-B.P. France

9 ROUXEL Charles Peugeot-B.P. France

10 AIMAR Lucien Sonolor-Lejeune France

11 GUYOT Bernard Sonolor-Lejeune France

12 HOBAN Barry Sonolor-Lejeune England

13 FREY Mogens Fornatic-De Gribaldy Denmark

14 DEN HARTOG Arie Caballero-Laurens Holland

15 POPPE Andre Mann-Grundig Belgium

16 VAN SPRINGEL Herman Mann-Grundig Belgium

|

|

In 1968 when Bodart scored his surprise win, I followed the race from Chatellerault where the riders made contact with their Derny pace-makers after 160 miles company riding from Bordeaux. Last year I simply went to the finish at Rungis to the south of Paris where Walter Godefroot won easily. On both occasions my report stressed the diminishing importance of Bordeaux-Paris which once really was a Derby in the sense that it attracted a field of top riders who had spent weeks and even months getting in shape for the 370 miles race. Nowadays it had become a consolation event for riders who for various reasons, had had a poor season.

Why, then, had I bothered not only to cover the race again, but to travel to Bordeaux to see it from start to finish ?

There are two answers to the question. The fuel is found in the list of riders engaged. True there were several who hadn't won anything during the season simply because they weren't good enough. But there were also those, like Barry Hoban and Herman Van Springel, who crashed during the Tour de France and were forced to retire when running into their best form.

Then there were three riders who had ridden very well as new professionals and were not riding this Bordeaux-Paris in desperation but with the aspiration perhaps not of winning this time - though obviously they would try - but of gaining experience for future campaigns. In this latter category were Leif Mortensen and Charles Rouxel (second and fifth at Leicester) and Mogens Frey who in July became the first Dane to win a Tour de France stage (Incidentally if he or Mortensen had won this Bordeaux-Paris it would not have been the first Danish success Ch. Mayer won in 1895).

The second reason I had come to Bordeaux was because an entirely new course was being used. Instead of some 300 miles along the wide, straight flat N.10 there was a roughly parallel route over secondary roads which was reported to be much hillier.

This change had not been made voluntarily by the organisers, l'Equipe and Parisien Libere. They had been told bluntly by the appropriate authority that if they wanted to hold Bordeaux-Paris this year, another course would have to be found. (I was not surprised to hear this; as we approached Paris in 1968 there were serious traffic problems).

The fact that the new distance was increased by 20 miles over last year's to bring the journey up to a record 382 was only half due to the changed route. An extra 10 miles was added through the 1970 finish being on the Municipals track in eastern Paris.

There were a few well laden team cars parked in and around the Alles Tourny in Bordeaux when I arrived on that Saturday afternoon 5th September. There was a meeting of the Directeurs Sportifs at 3 o'clock in the Maison des Vins, administrative and propaganda headquarters of the Bordeaux wine industry. I had a chat with Jean Stablinski, the French ex-world champion who now directs the Sonolor team. He told me I would just catch Barry Hoban at the nearby Continental hotel before he went out for a potter on the bike.

"How's Barry going ?" I asked.

"He's riding well enough - but not very quickly!"

I did not take too much notice of that remark. Stablinski as a rider was one of the most cunning in the business. As a Directeur Sportif he is no

|

|

less astute. Some rival ears were in our little group, and that reply to my question might really have been directed at them.

Barry's bike was outside the Continental hotel, so I waited in the lounge, which I seemed to recognise. Had I been here before ? Yes, I remembered. I was here on the eve of Bordeaux-Paris five years ago. Indeed Jean Bobet (in whose Radio-Luxembourg car I was to follow the race) had booked me a room in which to get a few hours sleep before the 2-30 a.m. start. So had several others, but nobody was anxious to go to bed. This was the famous night when, after winning the 8-day Criterium du Dauphind Libdrii, Jacques Anquetil took a special plane from Grenoble to Bordeaux with the intention of riding Bordeaux-Paris a few hours later. He arrived in the Continental restaurant where we were waiting in good spirits - and hungry. Three hours later he started Bordeaux-Paris which he won with Stablinski second and battling Tom Simpson third.

Before long Barry emerged from the lift, yawning.

"I've done nothing but sleep since I came here yesterday" he said -They say that Bordeaux-Paris is won in bed - in that case I'm in with a chancel"

"How is the form?"

"I just don't know. After the accident in the Tour on July 2nd I could not ride the bike for three weeks because of the three broken ribs. When I did start again it was tough going. My back aches terribly even in training, so you can guess what it was like in races over the pav6. Gradually the pain disappeared, but the form didn't come. With the idea of riding Bordeaux-Paris I have been riding an extra 60 kms home to Ghent after races in Belgium which built up my resistance, but I had no punch.

"Then the other day in a Kermesse I managed to get across 200 or 300 metres between the bunch and the breakaways. That was something like the real Hoban. Perhaps the form has arrived at last. But Bordeaux-Paris isn't an ordinary race. I like riding behind Derny pace, but I wasn't brilliant last Sunday in the Roue d'Or at the Municipaletrack."

Barry wheeled his bike round to the garage where mechanic Lucien was busy. Another Lucien (Aimar) was adjusting his saddle; Bernard Guyot was lounging on a pile of tyres looking pensive. I could guess his thoughts - those of one who had been a brilliant amateur but whose professional career had been disasterous. If he failed to make a show in this Bordeaux-Paris he might be without a marque next year ... Soon the three Sonolor riders set out for a potter together before returning to the hotel for more sleep and a 10 p.m. meal.

The "real start" was at 1 .a.m. at the traditional rendezvous Quartre Pavillons three miles north-east of Bordeaux. But first there were the hour or so of preliminaries in and outside the cafe Richlieu in the centre of the city.

It was a nice warm night, but all the riders were well wrapped up in a variety of woollies - all that is except Mogens Frey, bare of arms and legs. The TV lights and cameras were busy, radio-reporters too. I heard Barry Hoban correcting one "speaker" who had described him as a newcomer to Bordeaux-Paris "I started in 1964, my first year as a professional, but retired at Chartres." Among the fair-sized crowd I found Archer Road Club's Terry Ewing who has been riding well with a Bordeaux club and won five races; Terry was with the Northern Ireland rider David Walker an experienced rider in French events. I lick the pair and an English friend to have a chat with one of the Bordeaux-Paris field who had belonged to an English club - and I don't mean Barry Hoban.

"Yes" said Eddie Beugels of Holland, I belonged to the Kentish Wheelers for six months. I was over to learn English. I used to go up on the Southern Railway from Sittingbourne to Cannon Street every day with the city gents. I used to read the "Times" but did not get around to wearing a bowler hat. I worked in a laboratory. I enjoyed my time cycling with the K.W's. I even won a hill climb at Sundridge - it was steeper than anything we've got in Holland."

At half-past mid-night after much blowing of whistles and appeals to Messieurs les Coureurs Albert Bouvet led the procession of 16 over the Pont de Pierre for the neutralised ride to Quatre Pavillons, accompanied by hordes of bikes and mopeds. A ten minutes stop on the famous crossroads, then at 1 a.m. precisely they were off on the "new route" (in fact the first 120 kms was the same as that used in pre-war days before the construction of the bridge over the Dordogne opened up a shorter route to Angouldme).

Sixteen men on a 150 miles all-night ride and no need to look for signposts. About 100 yards ahead was a horizontal strip of six green lights the width of a gendarmerie car whose driver was matching the movements of two motor-cycling colleagues ahead following the plentiful Rustines direction arrows. (Rustines, puncture outfit and vulcanising kit makers, were again main sponsors of the race).

The odd man out of the 16 was the "stripped" Mogens Frey who soon found the night not to be as warm as he had imagined, with patches of mist gathering in the undulating road to Libourne. The Dane was soon making signs to his team car, third in the line of technical vehicles on the right of the road. We were in the leading cars in the left file. The Dane dropped behind us, to reappear a minute later snugly dressed like his companions with arm and leg warmers and a woolly hat.

Viewed from behind in a comfortable car the pack made a pleasant sight in the flood of light from our headlamps, the back plates of their pedals blinking back at us as they twiddled little gears to keep legs warm and supple.

|

|

They were out of the saddle on the slightest rise, for the idea behind a lot of "dancing uphill" is not to overcome the stiffness of the gradient but to prevent numbness and seat-soreness through constant saddle pressure. As on any clubrun there was a bit of larking around, Bracke and Bodart (two friends and neighbours from the Walloon area of Belgium) dropping off 20 yards then sprinting back for some imaginary prime. There were several other pairings during the night of riders from rival teams drawn together through language or friendship. Two pairs of new professionals, for instance: the two Danes, Mogens Frey and Mortensen, the two French boys Rouxel and Proust who had ridden so often together in amateur competition. They chatted together, they ate together (banana skins were frequently tossed into adjacent vineyards) and perhaps most companionable of all, they stopped together to satisfy personal needs.

The pedalling rate on the small gears and occasional stretches at 25 m.p.h. created the impression that the field were gaining on their 211 m.p.h. schedule. In fact they were down on it a lot. The explanation was that the mist was becoming very thick in patches. Until drivers realised they were now a nuisance rather than a help, the peloton had a ghostly look in the diffused light of the following cars' headlamps.

A feature of Bordeaux-Paris on the old route had been the night-long interest of the public. On my first contact with the race, in 1956, we talked with an old chap outside his roadside cottage and found he first saw the Derby in 1899 and had not missed one since. There certainly would have been scores of others with a similar attendance record, perhaps even a super-veteran who, as a child, saw the very first version in 1891.

How would the public react along the new course ? At first I thought the interest only slight, but soon every village was thronged with spectators. I noticed one poster for a Bordeaux-Paris ball: possibly there were others along the route arranged for dancing to go on far into the night until the imminent arrival of the race. And in one small town the riders were cheered on by a wedding party, complete with bride and groom who must surely have been as much in love with cycling as with each other. It was then half-past three a.m....

In the country too, they were waiting in smaller groups outside their homes often in dressing gowns or a variety of sleeping attire.

Was it worth staying up late before going to bed, or getting out of it in the small hours to watch 16 cyclists and a score of cars and motorbikes pass by in a couple of minutes? The answer will not really be known until next year if the race goes that way again.

Just after seeing the wedding party we became aware that although the 16 riders seemed to be on a club-run, they were under no obligation to remain on friendly terms. Vaguely and sleepily we had noticed Eddie Beugels drop from the bunch and behind us, presumably for a brief roadside stop. In due course back he came very fast, went right by the bunch and was away on the first cousin of an attack with 100 miles still to be covered before making contact with the Dernys at Poitiers.

Maybe it was because he was getting cold or just bored. Or perhaps it was a serious attempt to make rival teams work a bit harder while his own team-mate Bodart (who, remember, won in 1968) had an easy ride. At any rate little Bernard Guyot went after him, sat on his wheel for a few minutes, until with only a slight accelleration from the bunch, the pair were caught.

Despite this and one or two other similar skirmishes the five hours of darkness had put the race an hour behind the 211 m.p.h. schedule. It was well beyond Ruffec (starting point of the 21st stage of the 1970 Tour) before car lights were extinguished. Now the roadside spectators included lone hunters and shooting parties with their eager dogs, priests and communicants gathered on church steps, rugged peasants about to begin a long Sunday's overtime in the fields.

It was the beginning of another day for the riders, too. Just as he had been the last to put on warm clothing for the night, so was Mogens Frey the first to begin stripping off, the arm warmers for a start, then the leg. For the third time in two hours Van Springel made a certain sign back to his car, and by now he and his helpers had the Operation Penny drill off to perfection. Not a bidon, not a banana, not a spanner, just a ration of toilet paper. V.S. grabbed it, rode for a few hundred metres until he found a convenient spot to execute his urgent business.

We were now approaching Poitiers where the Derny pacers were waiting. In the seven previous Bordeaux-Paris events I had followed the "Derny town" had been Chatellerault and on each occasion I was there about half an hour before the take-over to enjoy the fun. The atmosphere was really something special, the tension building up as the riders grew nearer, the pacers literally running round in circles as they pushed Dernys into smoky, spluttering life. Then came the riders sprinting through the double row of spectators, but before settling down to serious work there was the

|

|

inevitable Bonjour shakehand between pacer and follower.

In the past it was possible for us to see all this in comfort and then follow on a few minutes later in the press cars knowing full well that for the next 100 miles the NA 0 was as wide as a motor-way with a load of room for us all. But in this 1970 Bordeaux-Paris the prise d'entraineurs was immediately followed by a -D- road which promised to provide traffic problems for a time at least. Accordingly our driver judged it better to move ahead just before Poitiers and for us to look back at what was going on. A wise decision. although the actual take-over point was on a wide by-pass road, we were soon on the narrow D3 looking back at 16 Dernymen, their followers, eight team cars, a personal van for each of the 16 riders, 16 reserve pacemakers, eight or nine official vehicles, half a dozen motor-bikes and passengers and a dozen press cars whose passengers apparently preferred such congestion rather than enjoy the freedom of the road ahead.

Often there is an immediate attack when the Derny-paced session starts, but today it was calm. Perhaps the riders were anxious about the extra 20 miles and were being cautious. Whatever the reason the effect was that they kept together riding at about 27 m.p.h. as compactly as they had on the 150 miles 18' m.p.h. clubrun from Bordeaux to Poitier.

At La Roche-Posay a banner across the road announced a RavItaillement - ter Service. In fact it was the third sitting of the Bordeaux-Paris feeds. The first two had been in the eight mile zones during which the riders were free to take on food and drink from their following cars. Now with the Dernys all together and on narrow roads, the feeding had to be done in relays, each team car moving up in turn with supplies of food and drink.

First to be served with their mobile late breakfast or early lunches (it was then 10-15) were Hoban, Aimar and Guyot of the Sonolor-Lejeune team.

Immediately the 13 miles feeding zone was over, Leif Mortensen attacked on a long hill - and the race had really started roughly mid-way between Bordeaux and Paris. He was chased by Van Springel and the speed shot up to nearly 40 m.p.h. when the plateau was reached. The 14 others were strung out in a long line the first to be dropped being Mogens Frey. an

|

|

ironical situation since the man responsible was his compatriot Mortensen.

It was significant, this reaction of Van Springel to the Mortensen attack. In 1967 V.S. had ridden Bordeaux-Paris and did not take an early attack by Van Coningsloo seriously. By the time he did, it was too late with the final result. 1 Van Con; 2 Van Spring. This time he did not mean to be taken by surprise.

Significant, too, was the fact that Mortensen's team car was soon up behind him with a radio appeal coming over for the reserve Bic vehicle to move up to take its place behind the ' peloton." After a spirited chase Van Springel caught the Dane, and not liking the look of each other the pair eased and were soon caught. The pace continued fast (30 m.p.h.) but regular through pleasant wooded country, with fields of ripening fruit, maize and grapes prominent in the more open spaces.

With the field compact the "second sitting" of food and drink was again performed in relays, during which time one or two reserve Derny pacers came up to relieve their No. 1 men who dropped back to a van to snatch a bite and a sip and also a can of oil for their thirsty engines.

The second feed over, the second movement began. In 10 kms young Proust had built up a lead of two minutes and the bunch could not have cared less. The Fagor boy had been one of the chief sufferers during the Mortensen-Van Springel raid, hardly able to maintain contact. His "attack" was clearly a suicide bid designed in some small way to help team-mate Perin who was third last year. Sure enough a slight quickening of the pace behind was enough to pull Proust back not only to the "peloton" but off it almost immediately, in company with the distressed Bernard Guyot and Ferdinand Bracke. What a tragedy for both these riders. The Guyot case I have already explained. As for Bracke, he had elected not to defend his world pursuit title at Leicester in order to train seriously for Bordeaux-Paris - and there he was a casualty with hardly a shot yet fired in anger.Even so there was already a stretcher case in Mogens Frey who fell after his pace-maker had touched another (Frey 's No. was 13 ...).

Meanwhile Barry Hoban had been sitting nicely behind his Derny and getting maximum shelter - the wind was negligible. Approaching Blois we thought of the tragedy in that town 11 months earlier when a distinguished pace-maker Ferdinand Wambst, who had starred in so many Bordeaux-Paris races, was killed in a track crash in which his follower Eddy Merckx was badly injured.

Enormous crowds cheered the field through Blois at the beginning of a beautiful 35 miles stretch on the southern bank of the Loire commanding views of stately castles. We jotted down other information tounstique in oyr notebooks. Rich soil, pretty cottages, flowers, plum and apples orchards, a couple of G. B. motorists wondering why they were being pushed on to the verge by motor-cycling police ...

There the recording of trivialities stopped. A new line of the note book for something important. in capital letters and a star:

*HOBAN ATTACKS!*

When Barry had a minute we were able to drop in behind. On our right was Race Directeur Jacques Goddet. "This is as it should be" he called out to me "An Englishman leading the Englishman's race!"

An Englishman G. P. Mills had won the first Bordeaux-Paris in 1891; in 1896 a Welshman Arthur Linton was joint first with Gaston Rivierre; in 1967 Tom Simpson took the Derby. Was Barry Hoban now on the road to emulating his late rival and friend ?

|

|

Barry looked strong and comfortable, hands on the tops, his front wheel only an inch off the Derny mud-guard. At Clery Saint Andre, with 103 miles still to go the lead was 2m 10s. Then I was startled to notice that there was no Sonolor team car behind our man. This meant, perhaps, that Stablinski had no confidence in Hoban and preferred to keep an eye on Aimar who was riding well. At length a van marked "Hoban" drew up behind its man, but over the short-wave radio we got news of the approach of a less friendly Van, Van Springel,and sure enough on the approach to Orleans he came up to and past the Englishman with a rush pursued by the tenacious Aimar. A sympathetic press colleague called from his car:

"Orleans never was a good place for an Englishman to be in!"

We could not have been many metres away from the scene of Joan of Arc's victory over les Anglats in 1429.

But Barry was not yet beaten Caught by Rouxel and Mortensen, he managed to renew company with Van Springel-Aimar, but almost immediately the Dane was dropped and was overtaken by his team-mate Rosiers. At length Barry lost contact, too. as Van Springel-Aimar began another passage of arms which soon put them out in front ahead of the second -tandern- Rouxel-Rosiers. For 20 miles the "accordian" was played. with Van Springel clearly the strongest and Hoban the weakest.

|

|

Here I must mention that on my first Bordeaux-Parts in 1956 I was impressed by the thorough way the clothing of the pacemakers was checked to see that no unfair advantage was gained by increasing the area of shelter. For this 1970 race the rules were the same; the stipulated clothing being;

One under-jersey

One racing jersey with long sleeves. If this has back pockets they must be sown up so as to be unusable.

One pair of racing shorts of the same type used by the bicycle riders.

One pair of cycling shoes.

One pair of black or white socks.

One pair of gloves, racing or ordinary, without sleeves. Muffs are forbidde.t.

One racing type of crash hat.

All this kit should be of the same size normally worn by the pacemaker.

|

|

I particularly checked these facts on noticing that one or two pacemakers had added some kind of plastic under-garment several inches of which was showing below the over-jersey. This obviously increased the bulk a little. It also has a fascination for one or two riders who could not resist the temptation of grabbing it. These brief sessions of fraud must have been invisible to the Commissaires who also appeared not to notice that one or two pacemakers seemed to have ballooned out a lot since Poitiers. One such was Aimar's ...

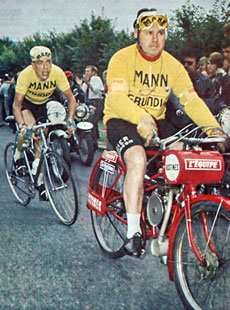

Aimar's Directeur-Sportif it will be remembered, is Jean Stablinski. The man in charge of Van Springel was Frans Cools a man no less astute, today he was not watching proceedings from a following car but was actually pacing his man. We learned afterwards that he realised Aimar was 'less at ease" behind his No. 2 pacemaker than behind the "Big One". Accordingly Cools made a premature stop to fill up with petrol from the following van, and was already back pacing Van Springel when Aimar's No 1 stopped for the same purpose.

And so "less at ease" behind the reserve pacemaker, Aimar was unable to reply to the violent attack which the intelligent Cools launched at the critical moment. It certainly was Cools' attack rather than that of Van Springel who shouted out for him to ease the pace. Had it been an ordinary pacemaker in front Van Springel would no doubt have been obeyed. But as this was his Directeur Sportif there was no arguing. They got rid of Hoban and Rouxel and above all of Aimar. Only Rosters remained, and he only lasted nine kilometres.

We dropped back behind Aimar and watched his furious chase to rejoin Rosters; the pair were now condemned to fighting for second place. Then we joined the motorized armada behind Van Springel, barring accidents, the certain winner of Bordeaux-Paris.

Until four years ago the final miles of the Derby were through the Valley of the Chevreuse before dropping down into Versailles. The demolition of the Parc des Princes in S.W. Paris and the transfer of the finishing area to the South or East of the capital has meant that only the fringe of the Chevreuse is now on the route.

There were great crowds out on historic Dourdan hill to applaud Van Springel, now 2 minutes 7 seconds in the lead gamning every kilometre, and steadily working his way through the ups and downs, the twists and turns on to roads which he knew well. He made contact with the Grand Prix of Nations course at a point where, in October last year, he was well down on both Poulidor and Agostinho, subsequently wiping out the arrears and going on to win the unpaved classic from the Frenchman by 29 seconds.

Behind Derny pace, the last 59 kms into the Municipals track were carried out in less haste. Time checks coming through showed the lead steadily increasing. Why take risks? On the hills Van Springel danced lightly through the crowds: on the descents he went fast but carefully, on the flat he was cautious, too, seemingly with one eye on the Derny mudguard, the other looking past Cools for any possible danger ahead.

|

|

And dangers there are in plenty on this difficult run-in to the ‘Cipale track which I described in a Grand Prix des Nations story two years ago.

On the few stretches of straight, flat road, Cools and Van Springel rode alongside for a hurried conversation. We could easily guess one of the subjects. Van S. was reminding his Boss that he was due to race tomorrow at Chateaulin in Brittany 400 miles away . . So take it easy!

Calmly and safely Van Springel rode towards the finish of the Derby. Smooth curved Tattenham Corners and stretches of "going good" were outnumbered by wickedly sharp turns and patches of badly surfaced road. More of a Grand National than a Derby, with the favourite out on his own and making sure he did not fall. Road traffic had been brought to a halt, but the sky was busy with jets going up and down from Orly airport just away to our right and the TV helicopter coughing and spluttering above.

We sped past Van Springel on the outskirts of Paris at Vitry-sur-Seine, along the river bank road with its pave and railway lines, over the Conflans bridge to the 'Cipale track. We only just made it as the triumphant Belgian party arrived on cement, Van Springel coming on behind Cools with the reserve pacemaker Devachter behind. After a lap and a half the two Dernys drew up alongside, with their gallant follower between them to cross the finishing line together.

Van Springel was all smiles.

The above five words are allocated a special paragraph because they record a rare occurence. Van Springel has so often been called the Buster Keaton of the pelotons, the man who never smiles. Indeed he shows emotion only on rare occasions. Such as Deep Distress on July 21. 1968 here on the same Municipale track when Janssen snatched Tour de France victory from him by 38 seconds in the last 20 minutes of the time trial. Such as Joy on now becoming the 20th Belgian to win Bordeaux-Paris.

Van Springel was also the first and probably the last Man to win the Derby , . The Mann team is withdrawing from team sponsorship at the end of the season. It will be hard for many of the lesser lights to get fixed up with another marque, though V S himself will have no trouble. Indeed it was being said that he would be joining up with Merckx in whatever colours he choses to ride in 1970.1 hope he doesn't. Merckx is in no need of somebody to hold his coat while he hands out his hidings. Better for the sport if Van Springel is among those who have a go at him I

Over the radio we had heard that Rosiers had dropped Aimar 15 miles from the finish, but it was the Frenchman who had finished the stronger after all to take second place. We were, however, without news of Barry Hoban who had been fourth when we left him reeling after the decisive Van Springel attack but he dropped two more places during the last punishing two hours. Further behind still was Mortensen who had crashed just outside the velodrome and rode the two lap of the track with a flat front tyre.

It had been well worth the journey to see the Derby on the new route from Bordeaux to Paris The hilly, narrow and twisting roads made it very tough: "A Derny paced cyclo-cross" as one mechanic said on the way out of the Velodrome

|

|

|

|

|

|

|