|

International Cycle Sport | April 1973 | Issue No 59 | Page 5 International Cycle Sport | April 1973 | Issue No 59 | Page 5

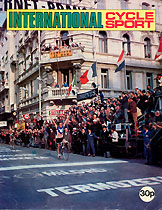

64th Milano-San Remo

by Aurelio Gadenz

SURPRISE surprise, San Remo hasn’t gone to Eddy Merckx this year as he was forced to be a non-starter due to illness, but his compatriot, Roger De Vlaeminck has become the temporary King of the Classics.

Its strange, the modern form of cycle sport, the way it revolves around Merckx, even when he is not riding an event, thoughts of him, and how he would have affected the outcome of the race is what everybody wants to write and read about. The eve of the Milan-San Remo was dominated by the sudden and unexpected news, that the worlds’ number 1 star rider had scratched and flown home to Belgium after having seen his doctor.

After Milan-Turin, the main events on the international calendar are both stage races, in France, the ‘Paris-Nice’, and in Italy, the ‘Tirrenno-Adriatico’, the race of the two seas. It was extraordinary that the races should both follow the same pattern as last year with Eddy Merckx again losing his white jersey of leadership on the time trial up La Turbie, to the ‘ever-green’ Poulidor, in Italy Roger De Vlaeminck had relegated all the Italians well down the result sheet to win the Italian stage race for a second time. Even the terrible weather of 1972 was repeated with the snow and ice playing a major part in the selection of the eventual winners. On hearing of Merckx’s troubles on La Turbie the Italian cycling journalists all wondered what had happened for Merckx to be relegated to 7th place in a time trial. Merckx eventually disclosed that he had been affected by a throat infection.

In short the non-appearance of Merckx meant a more open race for the ‘San Remo’. Many names were now put forward as a possible winner, both ‘sprinters’ such as Van Linden, the fastest finisher in Paris-Nice, Bitossi, Guimard, and the ‘hard men’ such as De Vlaeminck, Gimondi and Verbeeck. The Italians were hoping for a possible sprint victory from Basso who is enjoying fine form at the moment, and Raymond Poulidor was also down to ride.

The familiar scenery of the Castello Sforzesco was more crowded than usual as people who had come to look around the castle stopped longer to watch the signing on of the riders. I was walking around the Castello when Mr. Michelotti, the co-director of the race came up to me and introduced Mr. Haslett, from New Zealand, a member of the organising committee for the Christchurch Commonwealth Games. Mr. Haslett was here on business, but he was also reporting for New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation, and looking into the technical side of the organisation of cycle road racing.

We then awaited the arrival of Tino Tabak, a member of the Sonolor team. Tino is a Dutchman by birth, but has spent most of his life in New Zealand, hence Mr. Haslett s interest in this particular rider, but unfortunately the Sonolor squad did not turn up for the signing on, the same applying to the TI-Raleigh team, so we drove away from the castello to the hotel of the latter mentioned team. Milan was not as busy as usual because Italy takes a holiday over the weekend as Monday is St. Joseph’s day, and many Milanese had left the city for the countryside, but they will nearly all be there to swell the numbers of the tifosi along the race route.

The Hotel Canada where we were staying, although comfortable, provided no dining facilities, and not having been warned of this, George Shaw, the TI-Raleigh team manager had made no provision for a team of hungry athletes most of whom had only had a slice of cake on the motorway since leaving for the Italian capital. So it was the lone Italian of our small party (myself), who led the hunt around the streets for a meal for the riders and for food to eat during the race the following day. This was however, more difficult than it sounds, and nearly all the shops in the city were closed for the weekend, but after much searching we eventually satisfied the requirements of the riders and had a meal to everybody’s taste. The proprietress of the restaurant asked me how long it is since the riders had eaten, not knowing of the tremendous appetites of sportsmen! Before going to bed, I walked into the room which Harry Hall from the famous Manchester cycle shop had turned into a workshop, to prepare the teams machines for the race, as he was to be their mechanic on the race.

On the morning of the race we drove to the castle where we soon found a petrol station, probably open just for the trade they would get through the race vehicles. We went to collect the list of riders who were actually starting and then for the car boards which every vehicle connected with the race must display.

Before leaving Milan, another guest of the organisation was introduced to me, it was a former cross country champion and olympic gold medallist, Franco Nones. It is always a great thrill to talk to former champions, and before taking up ski-ing seriously he had beaten men of the calibre of Dancelli and Motta in cycle races. However, moving into the mountains curtailed his cycling career, but not his interest in the sport.

The 188 starters set off at 9-30 a.m. at the south of Milan. Usually the race starts very fast, but not this year, and after only 5 kms Dave Lloyd and Phil Bayton of the TI-Raleigh team were announced over the radio to have broken away from the main field. At first I could not believe it, since such good news for us was not expected. By 10 kms the break already had 1 min 10 secs and the bunch were not yet showing much interest. It seemed funny to me as I had explained before the start that normally it is very hard even to stay in the bunch and here they were trying their luck by now 3 mins 10 seconds ahead of the sleeping bunch. We then decided to drive ahead and wait at a convenient stopping place to watch the Raleigh tandem grind their way past us, the British boys having taken their chance were now getting their sponsors name on television and in the reports of European newspapers while the big names sat in the bunch.

After the duo passed us, we joined the lengthy entourage which had formed behind them and pulled alongside the TI-Raleigh team car which was being beseiged by press-men trying to find out more details of the two protagonists of the race. While we were asking the riders career details, Harry Hall was photographing them. ‘’How long do you think they can stay away’’ said one journalist, clearly not expecting them to stay much longer at the head of affairs. George Shaw need not have replied as the next time we received a time check, they had a massive lead of seven minutes. At Novi Ligure, they won a prime cheered by a large crowd who were having great difficulty in pronouncing the names of the Raleigh men. Not since Tom Simpson’s epic win in the 1964 version of this race had they seen anyone from England figuring in a break in an Italian classic, let alone two men from the same team! I believe that neither of them expected to reach San Remo still ahead of the bunch but they were intent on making a name for themselves.

About 90 kms had been covered and Bayton started to have a bad time, and he had to let Lloyd do most of the work. Bayton was out of the saddle on the flat striving to stay with the flying Lloyd. After 102 kms a dog ran across the front of the bunch, and brought down the German, Dieter Puschel, who was compelled to finish his race at the hospital. Following our now famous English friends, it seemed like the Baracchi time trial with Bayton now recovered from his bad patch and once more doing his share at the front,

While all the action and animation had been provided by the breakaway, the main field had remained intact, with the people who had punctures getting back to the safety of the bunch without too much difficulty. The first major obstacle of the day was now being climbed by Lloyd and Bayton, the famous Turchino pass, and only on the last 2 kilometres of the climb did they start to lose ground on the bunch behind. Despite the fact that they climbed the Turchino well considering they had been riding alone for more than three hours, the race director ordered all vehicles to go ahead of them as the bunch were now at 3 minutes 5 seconds. A kilometre from the summit, we overtook the break amid a deafening crescendo of cheering, from crowds lined up at the side of the road leaving only enough room to allow the cars through. Even the Turchino failed to light up the race in the bunch. and but for our lone duet we would have been watching a very dull race. I drove down the dangerous descent as fast as I could in an effort to keep away from the break.

We reached the coast after the descent, and were greeted by thousands of tifosi lining the road-side, and a shining sea both of which were to follow us to the finish of the race. After Voltri, Phil Bayton had the bad luck to puncture, and Lloyd waited for him whilst a quick wheel change was affected. At the next town along the coast road, Fabbri, of the Magniflex team was forcing the pace just off the front of the main field the Britons now had a lead of 1 min 30 secs. Fabbri was hauled back to the bunch and the next reaction came from Tumellero, and the Spanish national champion, Luis Ocana. Together the latest escapees worked until they had caught Lloyd and Bayton, who after more than 170 kilometres alone in front of the field were immediately dropped, soon to be caught by the bunch who realised the potential of a breakaway containing Ocana. The Spanish- Italian tandem, which was working quite smoothly, reached Pietra Ligure where a prime had been offered by a naval factory who’s workers had previously threatened to stop the race to demonstrate for better contracts with the firm. The race organisers promised to situate a prime outside the factory and asked them not to interfere with the race in any way. After the prime which was won by Tumellero, our car was asked to go ahead of the break as the bunch was rapidly closing the gap of 1 minute 10 sees which had been the most they had attained.

When the field entered the second feeding station, it was once more intact. Seeing such an easy race, I could not help thinking what Rik Van Looy the manager of the Ijboerke Bertin team was having to say, as after the Paris-Nice he had sent four of his riders home saying that they hadn’t ridden well enough to deserve a ride in a Classic. Once again two more riders tried their luck, both were from teams with very fast finishers, namely Houbrechts and Ritter of the Rokado and Bianchi-Campagnolo teams, with the sprinters Van Linden and Basso sat safely in the peloton. The break went on the Capo Cervo, and after a slow climb by the main bunch, the leaders descended to a 40 second advantage. The thousands of people lining the slopes of the Capo Berta climb must have been very disappointed to see all the strong men of the peloton hide their faces until the last few metres of the climb, where Verbeeck and Poulidor (where were the younger men) escaped very briefly. With only 20 kms to go the inevitable had happened and the break was caught. While all the action had been focused on the front the TI-Raleigh squad had suffered several misfortunes with George Shaw being rushed off his feet with a glut of punctures occurring in a short space of time. Harrison and Holmes having had to retire as they punctured when their service car had been following the Bayton-Lloyd break. Dave Lloyd was also unfortunate to puncture as soon as he was brought back to the bunch, but chose to retire though not yet exhausted. Despite that, no-one can take any credit from him and Bayton who was also dropped and forced to retire, as even Ocana who had only been away for a very short time compared with the Raleigh men had packed, content that he had shown his face to his supporters. Seeing that nothing looked likely to happen for a short while, I drove quickly away from the race and switched off my radio to allow my passengers a few moments of peace.

In fact the negative racing, the heat, and fatigue with having had to get up fairly early soon sent my guests to sleep. I awoke them at the bottom of the Poggio Climb, where we all hoped to at last see some real action on the final battleground before the finish on the Via-Roma. Last year also, the field had tackled the Poggio together but due to the higher race speed, only a few people were in the lead at the top. We thought that for all the racing that most of the field had done, the race this year might as well have started on the Poggio for just 9 kilometres to the finish. However the last 9 kms this year were enough to let the race live up to its name, as a superb battle was fought out as repeated attacks were launched in an attempt to lose the sprinters. Verbeeck and Ovion were forcing the pace, followed by De Vlaeminck, Poulidor, and Bergamo. At the top of the climb, the sprinters still had not been left too far behind, and the only possible result we could see was a sprint finish In the meantime, all the press and most official cars had gone ahead to the finish where the loud speakers were blazing out the last metres of the climb. On the descent, Francioni, a double stage winner in last years Giro launched an attack. Roger De Vlaeminck was quick to respond, but the move looked doomed when they were baulked by a television photographer on a motorbike. So fast were they moving that they were keeping up with the T.V. monitor who was doing his best to leave them behind. As we listened to the report of the descent we wondered if either of the leaders had a family to go home to as they plummeted down the descent.

|

Milano-San Remo 1973

|

|

1 Roger De Vlaeminck Brooklyn 6:53:34

2 Wilmo Francioni GBC At 0:02

3 Felice Gimondl Bianchi Campagnolo At 0:04

4 Henry Van Linden Rokado At 0:06

5 Patrick Sercu Brooklyn

6 Frans Verbeeck Watneys Maes

7 Parecchini Molteni

8 Franco Ongarato Dreher Forte

9 Cyrille Guimard Gan Mercier

10 Walter Godefroot Flandria

11 Franco Bitossi Sammontana

12 G Van Roosbroeck Rokado

13 Eric Leman Peugeot

14 Walter Planckaert Watneys Maes

15 Emanuele Bergamo Filotex

|

|

We did not know how one man could possibly hold off a bunch which was all over the road in pursuit. Gimondi probably trying to lead out Basso for the sprint gained a few metres only to find Basso was still in the peloton. He glanced around and knew that the only way he could possibly win now for his team was to go after the two leaders in a monstrous gear such as riders only of his calibre can turn after more than 180 kilometres. Gimondi began to cut away at the lead of the frantically working leaders who had now entered the last kilometre. With about 400 metres to go, Gimondi switched to the opposite side of the road to the leaders and hopes of a home victory were high, but De Vlaeminck countered the move and Francioni now desperately tired hung on to a well deserved second place with Gimondi’s magnificent finishing burst only good enough for third place. Even if we had not witnessed the best Milan-San Remo ever, we had got a result which one normally expects from a race of this calibre, with two big names in the first three positions. Van Linden won the bunch sprint holding off Patrick Sercu and Frans Verbeeck, with a tired Basso back in 23rd place, but still in the bunch which finished at 6 seconds. Van Linden could have won but for De Vlaeminck and Francioni risking life and limb trying to get around the motorcycle with the bunch blocked in for a few vital seconds, but Roger proved again that he could be the man to beat Merckx on an equal footing in the Classics. Many Italians were disappointed that their riders had not managed to obtain a "home win’’, but I think that they should be more optimistic as we had two new pros in the first 8 finishers. After the finish of the race, we went over to see the Raleigh team.

Despite the small number of finishers from their team, they need not be disheartened as their team had kept the race alive for all but the last bit. Eddy Merckx, who probably watched the race on television was probably sad having watched such an easy race, which he could well have won. Apart from 10 men, the bunch of 188 starters had all been promenading for many kilometres which was a great pity despite the tremendous finish to the event. Let is hope that Eddy will be back to race here soon: we prefer his races. |