|

International Cycle Sport | September 1972 | Issue No 49 | Page 5 International Cycle Sport | September 1972 | Issue No 49 | Page 5

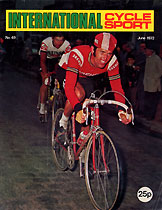

58th Liege-Bastogne-Liege 1972

There aren’t many records left for Eddy Merckx to chase after three seasons during which he has won an unprecedented number of major victories One of the most obvious targets for several seasons has been the Ardennes double, which fell to Ferdi Kubler in 1951 and 1952, and to Stan Ockers in 1955. As long ago as 1967 Merskx almost succeeded, losing narrowly at Liege to Godefroot after winning the Fleche Wallonne. For the last three years Merokx has been content to win the second race in the series, the one contributing towards Pernod Trophy and World Cup. After the Flandria squad had wrecked the first race in 1969 by ultra-defensive tactics, allowing Huysmans away to an unexpected victory, the first Ardennes race in 1970 and ‘71 fell to Roger de Vlaeminck.

In 1972 there were no De Vlaemincks riding either event: like all the Italian teams they had preferred to spend a few easy days riding Italian criteriums, a decision which elicited strong criticism in the Belgian cycling press, not only of the absentees, but of the UCI for not forbidding rival events on the same days as longstanding Classics. Not that it mattered, I suspect for the Italians had had a wretched season, while Roger de Vlaeminck was well content with his Paris-Roubaix victory of a few days standing.

The only other notable absentees were injured riders, Verbeeck and Godefroot and, despite fields of 141 and 152 riders, nobody doubted that Merckx was an odds-on favourite for both races. The only other rider to attract much support was Raymond Poulidor, while Dierickx and Rosiers seemed to rank equal third. Other names heard were those of Bracke, Van Malderghem and Van Roosbroeck. The most interesting here is Van Malderghem, little known in Britain, but with a strong following already abroad. In 1971 he won a stage in the Tour of Belgium, worried De Vlaeminck throughout the Dunkirk 4-Days and had several high places in top Belgian events. Of course, it was his brilliant ride in Paris-Roubaix, four days before the 1972 Liege-Bastogne-Liege, which led to his being listed among the favourites, a position which he owed also to the absence of Frans Verbeeck, absoloute monarch of the Watneys team: in his absence Van Malderghem and Van Roosbroeck would be settling the regency.

Kubler, Ockers . . . Now Merckx

By N G Henderson

In approaching Liege by road from the north, you pass close to the famous Rocourt track, for years traditional finishing point of both the Fleche and Liege-Bastogne-Liege, and also a venue in the past for world track championships. Now Rocourt was empty, for the race finish has been moved, the first not only from Rocourt, but out of Liege altogether. The drive into Liege soon showed why: roadworks and diversions everywhere, the centre of the town almost impossible to reach. In fact, on returning to Liege after the race in the "Figaro" car, whose driver had been going to the ironically named Hotel Britannique for 20 years, I was amused to note that he lost himself three times in the maze of side-streets pressed hastily into service as main roads.

In 1972 Liege-Bastogne-Liege was forced to finish elsewhere - not for the first time, for the race had already started and finished at Spa on one occasion. Now the choice fell on Verviers, a small textile centre 20 miles east of Liege on the Germany-bound motorway. Why Verviers instead of several larger towns more commonly associated with Belgian cycling 7 The answer is the usual one, that money talks, and the Cercle Cycliste Vervietois had guaranteed a handsome sum for the privilege of organising the finish of the world’s oldest surviving Classic. Through the industry of Jean Crahay, local club president, Verviers was beginning to make its name in cycling circles, Merckx having won a magnificent solo stage victory there in the 1968 Tour of Belgium. In 1969 it had been the turn of Roger de Vlaeminck to win the Verviers stage of the same event: club and town had obviously emerged with credit.

The main effect on the race was the omission of two famous climbs both now included in the Fleche Wallonne, and some alteration to the middle section of the route. The first feeding station was brought forward to Bastogne itself and an entirely new section was added shortly after Bastogne, while the distance between the worst hills - around Wanne - and the finish was greatly reduced.

The start was still in Liege, with the race control in the Chalet de la Boverie, on an island in the middle of the Meuse. First rider to arrive on the eve of the race was Eddy Merckx, picked up by the race organiser, and shortly followed in by his Molteni colleagues. After two hours only a quarter of the field had signed in, the rest preferring to wait until the following morning, when the control would be open until 10 am.

At 10 am there had been hardly any more although by now all journalists, drivers, judges and hangers-on had been accredited. The floodgates opened with 20 minutes to the start, as 80 riders crowded round the control-table. Among them was Barry Hoban, who was able to give me a first-hand account of his brilliant Paris-Roubaix. He wouldn’t go so far as to claim that he would have won without two critically timed punctures - while he was off the first time, two minutes adrift, Santy and Van Malderghem broke away; back in the leading group, he punctured again and made another fine return to find that De Vlaeminck had flown.

Barry admitted frankly that he was too tired by his second chase to pursue, or to accompany Dierickx on his belated burst, but that he was at peak form was obvious from his quick recovery, which allowed him to jump away in Roubaix to take third place. Certainly, from the radio commentary, it was obvious that Barry was one of the strong men of the race, and he deserved to become the best-placed British rider ever.

"Would I have beaten De Vlaeminck? I honestly don’t know. I’d have gone with him, that’s for certain. He might have given me a hammering on the cobbles, but I could probably have had I him on the track, because I was flying. You must remember that Dierickx and De Vlaeminck were incredibly lucky - they didn’t have any punctures in the last 50 miles - and nobody can win Paris-Roubaix without a fair share of luck."

And about Liege-Bastogne-Liege? Cautious I optimism was all I could get out of him, and a feeling that his own performance might well depend on Gan-Mercier leader Poulidor, who had come to win.

At 8 am the weather had promised much, but, by the time the convoy had put itself into some sort of order, a steady drizzle was falling and the sky looked uniformly grey. And so it remained as the advance convoy of press vehicles wound its way out of Liege, to await the race five miles up the road, at the first of 13 climbs counting for the King of the Mountains. For these few miles both sides of the road were lined by spectators, including the entire population of every school on the route.

As the field climbed smoothly up the long hill into Beaufays, the diminutive figure of Karl Heinz Kunde, the smallest rider ever to wear a yellow jersey in the Tour de France, could be picked out at the front. He stayed there all the way up, comfortably ahead of Georges Barras, who had been a late Molteni replacement for Martin van den Bossche. By the next climb, the first abortive solo had begun, and Mat Gerrits (Goudsmit-Hoff) led by 20 seconds. with Rokado’s Kunde still leading the bunch. Now the first long descent came, and a radio instruction for press cars to get a move on, or the riders would be among us, as we screamed down and around bends - which would become an accustomed routine as the day wore on.

So far, the road had been broad and smooth but this was shortly to change, as we swung away in Aywaille to greet the sun once more. There must be something about fine weather, for the tempo increased at once. in spite of the poorly surfaced, sinuous road. Gerrits, and others like him, were quickly picked up, but the attacks continued: next to go was Eric Wyckaert (Novy-Dubble Bubble), first up the third climb from Barras. The race had already gained five minutes on its expected 36 kph schedule in 22 miles.

This didn’t last long, for the sun vanished again, and the pace again slowed. We were now in Luxembourg province, following the magnificent valley of the Ourthe through Barvaux, after which the route led to an even narrower road and the only serious accident of the day. Jan Janssen and Harry Stevens fell heavily at a point where the road was so narrow that it was barely possible for the service cars to get through, let alone an ambulance. Needless to say the ambulance squeezed through, and sped off to Bastogne.

For several miles the race was very quiet, and relatively slow: various team managers appeared to be having their own race, trying to steal places in the convoy despite the convoy numbers which they had drawn from a hat earlier that morning. Guillaume Driessens, now Magniflex boss, could regularly be seen nosing ahead, and one wondered what he was plotting now; he it was in the 1969 Fleche Wallonne, as Merckx manager, who had coincidentally stalled his car right in front of Roger de Vlaeminck as Merckx and Van Schil burst away on the break that was to bring them to the finish eight minutes clear. Whatever his reasons now, nothing came of the manoeuvring. Attention switched back to the serpentine column of riders who appeared over the horizon like the US cavalry rushing to relieve a besieged fort, as the cars swung down and left to offer this magnificent panorama.

At La Roche, tourist capital of the Ardennes and 40 miles from the start, there was still nothing of note, but the first serious attack went straight out of the town. Up the long climb to Ortho Agostinho, Letort and Ward Janssens broke away, with Kunde taking his last climbing point of the day. By Bertogne the bunch was closing, and Jean van Buggenhout and Claudine Merckx, making the first of their many criss-cross visits to spy on the race, were able to note the Rainbow Jersey very much in command. All the way to Bastogne, as fast as a break was pulled back another formed, usually with the entire Bic and Moltem teams in charge. At one point Guy Santy (Bic) could be seen towing Merckx and four more Moltenis to a 100 yards lead, but Bastogne was reached with the bunch intact, once more five minutes early, once more under a welcome sun, which was to stay with the race for the rest of the day.

Five miles of wide boulevard followed the feed, and then came the new, and unknown section and, almost immediately, 50 yards of road with no surface whatsoever. Panic! Poulidor, Dierickx, Thevenet were among the victims here, and it was surely no coincidence that Merckx chose the next hill, two miles on, to launch his first attack: 50 yards, a 100 yards, a slight dip and another climb to cross the summit 300 yards clear of Letort and Pintens, who had Swerts sitting in. Zoetemelk and Poulidor led the bunch, with Huysmans immediately behind. Everything that moved had a Molteni tail from now, and this lasted to the very end of the race.

Merckx had decided to make the race harder, so his lieutenants took their turns in forcing the pace. The lead over the schedule crept up again, although the race record, the oldest of all dating back to Richard Depoorter in 1943, was never threatened. Spruyt led over the fifth counting climb, supported by In’t Ven, and, at last, the split occurred. Suddenly there were 44 riders in the leading bunch, 20 chasers at half a minute, and the other half of the field had had it. The first move had succeeded, exactly as in 1971. Then, after the field had split, every aggressive move saw a Molteni rider sitting in until, finally a break succeeded and formed a platform for Merckx’ latest assault.

To the delight of the chief judge’s passengers, it was Tabak who initiated the break in 1972, allowing a succession of smoke-laden puns to waft over the radio. The Molteni rider with him was Mintjens: with 60 miles to go they were 20 seconds up. six miles later the lead was 2’45, and Mintjens was happy to allow Tabak to lead him all the way up climb number six under a glorious tunnel of evergreens, the chase being led by Poulidor, with Hoban and Merckx well tucked in.

Into and out of Trois Ponts, along the Circuit des Panoramas. the lead fluctuated around two minutes. The next climb, Mont St. Jacques, was the hardest yet, bringing the leaders to within 1’20, Merckx following Wim Schepers to take his first climbing point of the day. We were now nearing the point where, in 1971, Merckx had begun his chase. No sooner had this thought occurred than the news came over the radio that Merckx, Van Springel and Schepers were away from the bunch and belting after the press cars into Lavaux. As we entered the village the warning-lights on the level-crossing began to flash. All the cars crossed safely, and down came the barrier, fortunately only for a light engine travelling fast. The barrier had barely risen when Tabak and Mintjens came through, with the chasing trio some 20 seconds down, and the same margin dividing them from the bunch. Back on the traditional route, the junction was made inside four miles, just before the foot of the infamous Cote de Wanne. Thirty seconds at the foot became 45 at the top, with Mintjens, his job done, free to slip back to the bunch and eventual retirement.

The next hill, Stockeu, was the point where Merckx left the 1971 break, but now this same hill was only 30 miles from the finish. Of all the Classic hills, this is probably the most vicious, only four miles after the hard Cote de Wanne, and approached by a completely dead right-hand turn, leading into an initial gradient of 1-in-7. It is a hill which is climbed purely for the sake of climbing it; the route brings the riders out on the next road, at the same junction as the dead turn. Instead of the sudden acceleration of 1971. Merckx went for a gradual wearing down, disposing first of Tabak, then of Van Springer finally of the resilient Schepers. Twenty seconds lead over Schepers at the top, and one minute over the bunch, where Pintens was trying desperately to escape from Van Schil, Mortensen from Swerts, Delisle from De Schoenmacher. Unhappily, Poulidor and Dierickx had both punctured again, and the radio service to team managers did not give news of the actual racing. Dierickx packed immediately, but Poulidor made a quick return to the leading bunch, only to find that Merckx had flown, so Poulidor also decided that he had had enough for that day.

|

58th Liege-Bastogne-Liege 1972

Route: Liege -Barvaux -Ortho

-Bastogne -Wanne -Spa -Vervier

Distance: 149 miles

Race speed 36.488 kph

Record = 37.679 (1943)

|

|

1 Eddy Merckx (B) Molteni 6:33:23

2 Wim Schepers (NL) Rokardo at 2:40

3 Herman Van Springel (B) Molteni at 4:35

4 Roger Swerts (B) Molteni at 5:26

5 George Pintens (B) Magniflex

6 Leif Moertensen (DK) Bic

7 Roger Delisle (F) Peugeot

8 Gilbert Bellone (F) Rokardo at 6:38

9 V Van Schil (B) Molteni

10 Roger Boloux (F) Peugeot

11 Bernard Thevanent (F) Peugeot

12 Barry Hoban (GB) Gan Mercier

|

|

King of the Mountains

1 Eddy Merckx 29pts

2 Wim Schepers 24 pts

3 Herman Van Springel 12 pts

|

|

At the top of the next climb, only two miles further on, Merckx had a minute over Schepers, whom Van Springel had rejoined, with Perin, Van Schil, Tabak, Pintens and Alain Santy at 1’55. The race was now over, barring accidents. For a couple of miles the gaps narrowed, as Merckx eased to drink copiously, but the climb from Francorchamps to Le Rosier rectified the situation: 1’25 and 2’35, with 19 riders closing on the five. Again Van Springel was dropped, and again he caught Schepers on the descent, for them to cross Spa together, but the climb of Annette et Lubin saw him off finally, leaving the astonishing Schepers in sole pursuit, while the Belgian champion struggled to protect his third place.

From the bunch of 19, Pintens finally broke away, helped by Delisle, and guarded by Swerts. Although the race at the front was virtually won, there remained the closest in-fighting for the places d’honneur. Next to move up was Mortensen, widely tipped as the likely winner of the Tour of Spain, but it took four miles of agonising pursuit, with the Pintens group never out of sight, before Mortensen could join Swerts at the back of the little bunch, now 4’50 down on Merckx, whose lead over Schepers and Van Springel was 2’30 and 2’55 respectively.

All the work in the chasing group was being done by Pintens, with Delisle occasionally alongside him and Mortensen trying in vain to break away up the last climb, five miles out of Verviers. Further back, the survivors were splitting up, retiring, forming and re-forming alliances, but all to no avail. At the line Merckx had marginally increased his lead over Schepers, Van Springel had held at bay the quartet, and Swerts convincingly won the sprint for fourth place. If anybody had doubted the strength of the Molteni team after the disappointments of the Tour des Flandres, Ghent-Wevelgem and Paris-Roubaix, all doubts were resolved during this triumphal procession towards Verviers. |