|

International Cycle Sport | September 1968 | Issue No 5 | Page 10 International Cycle Sport | September 1968 | Issue No 5 | Page 10

ALLEZ LE BRITANIQUES!

By J B Wadley

TEN at the start at Vittel. Four at Paris. So far as numbers are concerned that was a record for a British national team.

- In 1955 we had two finishers. Brian Robinson (29th) and Tony Hoare (69th)

- 1956: only Robinson, a member of the International team lasted out (and finished 14th)

- 1957: Robinson started in the International team. but retired after a crash

- 1958: Stan Brittain (International team) was 69th and Shay Elliott (Ireland - but on Brittain's team) 48th

- 1959: Robinson (19th) and Vic Sutton (37th)

- 1960: Robinson (26th) and Tom Simpson (29th)

- 1961: Elliott (riding for GB) 47th, Robinson (53rd), Ken Laidlaw (65th)

Trade Teams:

- 1962: Simpson (Gitane-Leroux) 6th, Alan Ramsbottom (Pelforth Sauvage-Lejeune) 45th

- 1963: Ramsbottom (Pelforth S-J) 16th, Elliott (St Raphael) 61st

- 1964: Simpson (Peugeot) 14th, Michael Wright (Wiels-Groene Leeuw) 56th, Barry Hoban (Mercier) 65th, Vin Denson (Solo Superia) 72nd.

- 1965: Wright (Wiels-Groene Leeuw) 24th, Denson (Ford) 87th

- 1966: No British finishers

National Teams

- 1967: Hoban (62nd), Arthur Metcalfe (69th), Colin Lewis (84th)

- 1968: Wright (28th), Hoban (33rd), Denson (62nd), John Clarey (63rd)

The selection of Hugh Porter in the British team was a gamble which might well have come off. For one of the world's best pursuit riders, the distance (3.8 miles) of the opening time trial was such that Hugh could have taken the Yellow Jersey on the first night. Had it not been an "out and home" affair, or on a gentle circuit with few corners, then I think he would have succeeded. In fact it was an "acrobatic" course which put the tall Britisher at a disadvantage. I am convinced that Porter was not 15 seconds slower than Grosskost on pedalling time, but lost it on the bends and corners.

Had Porter taken the Yellow Jersey he would -as things turned out have lost it the next day, owing to his painful foot. Without that misfortune, which caused his retirement on the road to Forest, I think Porter would have lasted through at least until Bayonne. The slow pace of many of the stages, ending with a ten-mile tear up with a finish on a cement track, would have suited him admirably.

Later in this issue Geoffrey Nicholson makes the point that normally a puncture or change of bikes is merely a routine affair, but that which caused Colin Lewis's elimination came when the battle was on. But for that trouble Colin would certainly have gone on and on, not only to Bayonne, but to Paris - and Britain would not have been last in the team race. Derek Green, however, is not a Tour de France man distance-wise, although his class is certain. In fact Barry Hoban was full of praise for his intelligent riding in the first few stages. Derek's stage race limit is probably seven or eight days the distance of Paris-Nice or the Tour of the West.

Bob Addy is another who might well have finished in Paris, but for the two falls on successive days with the Pyrenees in sight. At the same he was recovering his strength after a bout of stomach trouble All the team worked well together and unselfishly in "rescue operations" in time of punctures or mechanical trouble, and none harder than Bob.

The case of Arthur Metcalfe is more complicated. Compared with last year, when he was looking thin and drawn after a few days, Arthur found the first week quite easy, and was looking forward to putting up a good show in the Pyrenees. Then on the day before the Pyrenees foothills had to be tackled - a stage which was taken quietly by anybody with mountain aspirations - Arthur made his now celebrated lone breakaway on the road to Bayonne.

Whatever the reasons behind the attack, I thought at the time that it was a mistake, especially when I saw that Metcalfe was not moving at all smoothly. The unaccountable weakness, which gradually increased and eventually caused his retirement, had apparently already hit Arthur before his attack had even started. That attack, then, was not entirely responsible for his lowly placings in the Pyrenees. (Next day Lopez Carril, who was runner-up to Metcalfe in the 1964 Tour of Britain was away on an 80 miles lone break for which, we thought, he would pay next day. Instead he was one of Poulidor's companions on the eventful Tourmalet stage and finished fourth).

Mention of Poulidor brings me to Britain's sixth retirement - Derek Harrison. There seems to be a jinx over Derek in big stage races, just as there is over Poulidor. He had just emerged the best climber in the Tour of Switzerland, was in excellent shape, and intending to ride comfortably down to the far Turn, then begin serious work in the Pyrenees. The crash between Roubaix and Rouen ended his dreams, and I reported last month how he retired next day.

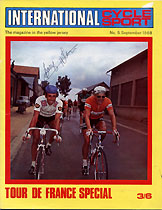

Our front-cover boy Barry Hoban, rode an excellent Tour. One sensed that he was out to show the world that the "gift" win last year the day after Tom Simpson's death, would not be the only time his name appeared on the Tour record list. In some respects Barry had another gift of five minutes or so on his successful attack between Grenoble and Cordon, for the bunch thought his absence was due merely to his anxiety to collect the "Hot Spot" prime for the day. But there were few riders in the Tour with the physical ability to time trial for 70 miles over two major cols, with a final four-mile uphill slog to the finish. Indeed, one can imagine riders just lasting out to get the Souvenir Henri Desgranges prize at the top of the Col des Aravis, then blowing up and finishing 15 minutes down on the winner.

The most disappointment moment of the Tour came at Auxerre where we saw Michael Wright just beaten into second place. It was here three years ago that Michael won his first stage, and a popular repetition of history seemed certain. But even this set-back did not ruffle the most phlegmatic of the Britishers. If you have read that Michael said he would have won but for that slow puncture, he has been misreported. He refused to say any such thing. The conversation at the stage finish went like this:

"But for the 'flat' you would have won, Michael ?"

A shrug of the shoulders in reply.

"But you are faster than Leman."

"As a rule, yes. But today he was very strong."

This, of course, was in French! Incidentally, when Michael finished at Grenoble he had a mike thrust in front of him and a British TV news man asked him, in English, what he thought of the day's racing ! The tabulated results at the back of the book show how well and consistently Michael and Barry sprinted during the Tour, and how much they contributed to the team's overall earnings of about £2,500.

The last men in the gc table are by no means the least. It was Vin Denson really, who made history when he timed a break so perfectly on the Auxerre stage that he helped Britain gain her first-ever team win (In 1959 Robinson, Sutton and the Austrian rider Chistian won for the Internationals). Denson was, of course, a valuable man not only to have in the peloton, but in the restaurant and hotel at night. His vast experience, advice, and general good nature, played a great part in keeping up the morale of the team. One would think that Vin had now been long enough in the business to find it all a bore. But he enters into the spirit of the race with all the enthusiasm of a complete newcomer.

Last month I paid a tribute to John Clarey, who between ourselves, I did not think would last out until Paris. And in "ourselves" I included John, who didn't think so either! When Tony Hoare finished "Lanterne Rouge" in the 1955 Tour, he was thanked heartily by Brian Robinson. Tony hadn't been much good to Brian on the road; while the one was up somewhere among the leaders, Tony was off the back calculating by how much he would beat the time limit. But his good nature and cheerfulness had kept Brian happy at nights - and probably kept him in the race, too.

There was something of the Tony about John Clarey, not merely because they both had the same track background, but because their temperaments are similar. The most memorable quote of the Tour came from John after he had finished fifth in the big Bordeaux sprint: "I was so astonished and overawed at passing Janssen and Bitossi on the last banking that I forgot to sprint for a few seconds . . . "

At the start of that stage Vin Denson told me that the Rest Day they had just had at Royan, was the most enjoyable of any stage race he had ever been in. It was a happy circle. Here we had fellows who got on well together off the bikes, working together as pals on the road and as a result becoming even firmer friends after the stage was over.

In the team, of course, we must include mechanic Ken Bird, chief soigneur Rudi Weideau and above all, manager Alec Taylor. I believe that if Alec had been given a free hand and a bit of money to spend, he could, by 1970, have produced a Tour de France team capable of finishing in the first half, with its leading member in the first half-dozen on individual classification. For this reason alone, I hope the reversion to trade teams for 1969 is only temporary so that we may see Alec again in charge of our national team.

And now, on the following pages, you can read a potted history of the 1968 Tour de France. Please do not consider each day's paragraph as a report. You may indignantly exclaim, for instance, that we have said nothing on a particular day of Metcalfe's change of bicycle, or Addy's two punctures, of Hoban's fall or Wright winning a big prime. By necessity we have only made such points when they really influenced the race. Two or three complete pages would be needed to record all such incidents throughout the Tour.

|